The Most Underrated Speculative Fiction Writer of the 2010s is... Scott Alexander?

Why speculative fiction should pay attention to Substack's favorite intellectual

My favorite active speculative short story writers by quite a large margin are Ted Chiang,

, and Scott Alexander. The first two names shouldn’t come as any surprise, as Chiang and Liu are the two biggest names in the genre right now. But… Scott Alexander? Isn’t he just some essayist?For those unfamiliar, Scott Alexander is a Bay Area writer known for his blog Slate Star Codex, as well as its successor on Substack

. These outlets are difficult to classify. Alexander describes the subjects of his own writing in two ways: poetically (“a sort of hidden node at the center of art and harmony and rationality and the rest”) and pragmatically (“reasoning, science, psychiatry, medicine, ethics, genetics, AI, economics and politics”). These descriptions certainly suffice for a curious potential reader, but neither of them really get at what it’s like to read Scott Alexander.Quillette described Scott Alexander as “Philosopher-King of the Weird People”, and this gets us a bit closer to grokking what type of writer he is. Alexander’s readership includes quite a few famous people, but they are unmistakably on the “weird” side of famous: nerdy individuals who are perhaps more influential than they are household names. Think Sam Altman, Steven Pinker, Andrew Yang. Your favorite intellectual’s favorite intellectual, if you will.

Just as idiosyncratic as his readers, Scott Alexander writes on interests spanning from the ethnogenesis of America to the effectiveness of ivermectin in pieces that are equal parts approachable and esoteric. Fiction is well within this wide umbrella of interests, with Slate Star Codex hosting a respectable 36 short stories. But while Alexander is both an influential writer and a speculative fiction writer, he is rarely acknowledged as an influential writer of speculative fiction. In most discussions where Alexander’s name comes up (among non-fans), his fiction is completely overlooked.

I was able to confirm this discrepancy somewhat when I actually met Ted Chiang and asked him about Scott Alexander’s fiction. I was curious because Chiang is someone who straddles the line between tech and literature, so I was fairly sure he had at least heard of the man. Chiang had indeed heard of Alexander, but he was also completely unaware of any fictional output.

Even though I had my suspicions, I was still surprised to see how much Alexander’s fiction was overshadowed in practice. Slate Star Codex didn’t get popular because Alexander is a marketing genius; it got popular because its quality was undeniable. There is much less attention on fiction than nonfiction, but I figured Alexander’s stories had enough eyeballs on it at this point for them to become known. Especially by someone who is at the center of speculative fiction centers right now.

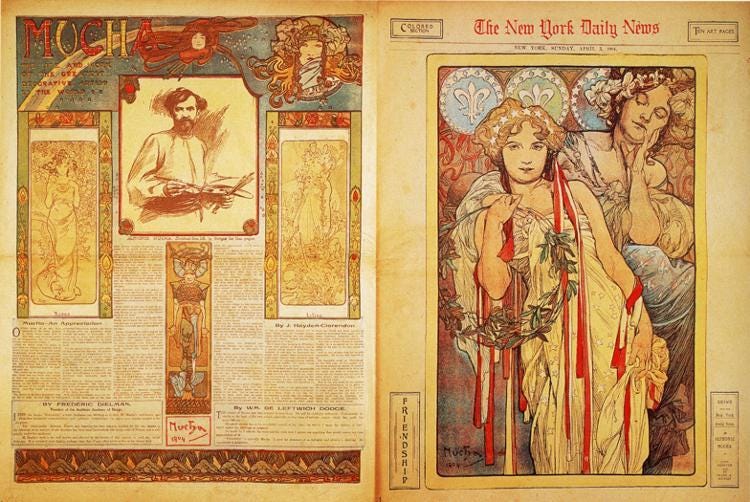

In the end, Alexander’s fiction remains outside of the public eye because it is not appreciated by the right people. Since people read so few works of fiction in general, prestige is determined not by popular will but by institutions. Far more people read AO3 than n + 1, but that doesn’t mean the latest Steve Harrington x Eddie Munson smut fic is going to get a review in the New York Times. Our cultural gatekeepers are tasked with separating the highbrow wheat from the pedestrian chaff.

But Alexander’s fiction is interesting because it is highbrow, just not in a way that is legible to our literary institutions. It certainly doesn’t read like the kind of fiction that would be published in The New Yorker or Strange Horizons1. With that in mind, I’d like to introduce three different lenses for understanding the appeal of his stories to a more casual audience. Hopefully this will shed some light on why Alexander’s stories are so hard to classify, which is inextricably linked to why they are so special.

I: Hard SF Minus the Hard SF Aesthetic

The term hard SF tends to conjure up a certain kind of aesthetic experience. We think of being dazzled by navigational charts, refinement processes, or the inner workings of a supercomputer. This is often more enjoyable when full understanding is just out of reach. The few things you understand make you even more appreciate of the things that you don’t, immersing you in a state of technological wonder.

Alexander’s fiction is not hard SF in that sense. He will not dazzle you with orbital mechanics, planetary governance, or alien biology. Not only do his stories forego the main tropes of the genre, but they also don’t appear to take themselves very seriously. At first glance, they seem more like a koan or a joke. But if a reader is able to look past all that silliness, a certain hardness does eventually reveal itself.

One of our podcast guests defined the hardness of a piece of speculative fiction as the extent to which it takes its own premises seriously, rather than its scientific rigor. In other words, does it really consider how its setup would set the story in motion? Or was the setup just slapped on top of some cute plot as an afterthought?

Under this definition, Alexander’s speculative fiction is about as hard as it gets. His most famous short story “…And I Show You How Deep the Rabbithole Goes”, has a rather silly and non-rigorous inspiration for its premise: a Tumblr quiz about pills that bestow superpowers. But the story takes this premise very seriously:

After a few weeks of downtime while you wait for your leg to recover, you become a fish. This time you’re smarter. You become a great white shark, apex of the food chain. You will explore the wonders of the ocean depths within the body of an invincible killing machine.

Well, long story short, it is totally unfair that colossal cannibal great white sharks were a thing and if you had known this was the way Nature worked you never would have gone along with this green pill business.

You escape by turning into a blue whale. Nothing eats blue whales, right? You remember that from your biology class. It is definitely true.

The last thing you hear is somebody shouting “We found one!” in Japanese. The last thing you feel is a harpoon piercing your skull. Everything goes black.

—Scott Alexander, “…And I Show You How Deep the Rabbithole Goes”

I really like how Alexander starts with the impression that he’s going to be a realist killjoy. The fun yet uninspiring first few sections inspire the thought, “okay, Professor Alexander, I guess that is what would happen”. A reader might accuse Alexander of missing the point at this juncture: he’s taking it too literally, he doesn’t understand the whimsy of the question. But you soon realize that this literal interpretation allows Alexander to create far more whimsy than you would have ever imagined.

Some may dispute my speculative fiction classification, so I would first like to argue that there is something very pure about the “speculativeness” of Alexander’s fiction. Since Alexander has built his reputation on being an earnest truth-seeker, his stories must be understood in that context. Fact or fiction, Alexander’s writings are meant to go towards clarity, to make sense out of chaos. In this regard, they are quite satisfying.

It may not look like typical speculative fiction, but Alexander’s “seriousness about silliness” actually gives his fiction a very pure speculative quality. It allows him to focus less on the aesthetics of speculation and more on the actual speculating. In the early days of science fiction, even to just imagine a rocket ship was a dramatic act of speculation. But now that rocket ships exist, you can write a fair bit about rocketry without doing much speculation at all! In contrast, weird setups like the pills create a fresh fictional canvas with emergent speculative properties.

In the end, Alexander’s disarming speculative fiction is a good fit for an age in which technology often feels more overwhelming than empowering. The standard style of hard SF comes from a time when there was more optimism about technology, which can make it feel sterile and dry. In a world where so many technological aspirations have failed to live up to their promise, it can be refreshing to receive speculation in a more playful package.

II: Jewish Fiction for a Secular Age

If I had to give a title to Scott Alexander debut short story collection, I would call it Much More Than You Needed to Know. This is a tagline that appears in the titles of his exhaustive fact-finding posts, and this same exhaustive quality defines much of his short fiction. In particular, there is a fascination with clearly-defined rules and how they can be read and interpreted to reach counterintuitive conclusions.

Alexander may be Jewish, but his writing doesn’t exactly scream religious. It is not especially pious, confessional, or apologetic. At first glance, it seems more reflective of Enlightenment ideals, perhaps some form of secular humanism.

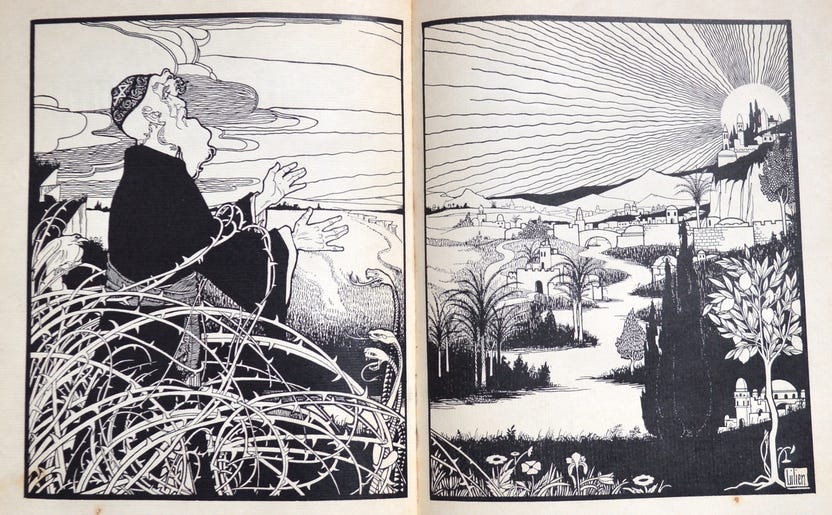

But his fiction fits into the broader canon of Jewish fiction surprisingly well. His fiction’s convoluted dynamics echo the Chelm stories and the tales of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Alexander appears to be secular, but it is easy to imagine him as a rabbinic scholar in a past life, seeming as though he is trying to “pull a fast one on God”.

Many of his stories read like a tortured Talmudic dialogue, taking some set of rules far beyond its intended context. Consider this story about a group of islanders who have to kill themselves once they can determine their eyes are blue:

“You know what?” said Enuli. “I’ve always wanted to say this. ALL OF YOU GUYS HAVE BLUE EYES! DEAL WITH IT!”

We nodded. “You have blue eyes too, Enuli,” said Daho. It didn’t matter at this point.

“Wait,” said Bekka. “No! I’ve got it! Heterochromia!”

“Hetero-what?” I asked.

“Heterochromia iridum. It’s a very rare condition where someone has two eyes of two different colors. If one of us has heterochromia iridum, then we can’t prove anything at all! The sailor just said that he saw someone with blue eyes. He didn’t say how many blue eyes.”

“That’s stupid, Bekka,” Enuli protested. “He said blue eyes, plural. If somebody just had one blue eye, obviously he would have remarked on that first. Something like ‘this is the only island I’ve been to where people’s eyes have different colors.'”

“No,” said Bekka. “Because maybe all of us have blue eyes, except one person who has heterochromia iridum, and he noticed the other four people, but he didn’t look closely enough to notice the heterochromia iridum in the fifth.”

“Enuli just said,” said Calkas, “that we all have blue eyes.”

“But she didn’t say how many!”

“But,” said Calkas, “if one of us actually had heterochromia iridum, don’t you think somebody would have thought to mention it before the fifth day?”

“Doesn’t matter!” Bekka insisted. “It’s just probabilistic certainty.”

“It doesn’t work that way,” said Calkas. He put an arm on her shoulder. She angrily swatted it off. “Who even decides these things!” she asked. “Why is it wrong to know your own eye color?”

“The eye is the organ that sees,” said Calkas. “It’s how we know what things look like. If the eye knew what it itself looked like, it would be an infinite cycle, the eye seeing the eye seeing the eye seeing the eye and so on. Like dividing by zero. It’s an abomination. That’s why the Volcano God, in his infinite wisdom, said that it must not be.”

“Well, I know my eyes are blue,” said Bekka. “And I don’t feel like I’m stuck in an infinite loop, or like I’m an abomination.”

“That’s because,” Calkas said patiently, “the Volcano God, in his infinite mercy, has given us one day to settle our worldly affairs. But at midnight tonight, we all have to kill ourselves. That’s the rule.”

—Scott Alexander, “IT WAS YOU WHO MADE MY BLUE EYES BLUE”

Scott Alexander’s fiction can be exhausting, but I say that in the best way possible. He ties you into knots, but not without inspiring faith that he will be there to untangle you at the end.

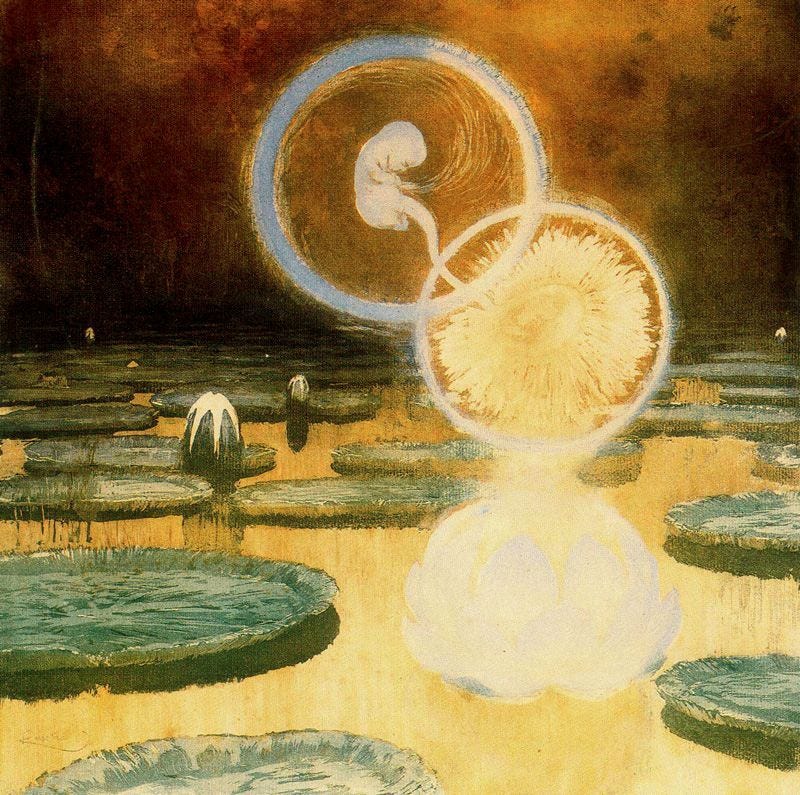

Of course, it would be misleading to ignore Scott Alexander’s only novel, which talks about Judaism explicitly at length. UNSONG is a speculative novel about an alternate timeline in which a school of Jewish mysticism ends up being empirically verified. In typical Scott Alexander fashion, the timeline of UNSONG diverges from our own when the Apollo 8 mission is not in fact able to orbit the Moon and instead smashes into the archangel Uriel’s celestial sphere.

Ever the realist, Alexander imagines the emergence of a gigantic megacorp called UNSONG that tries to uncover the divine names of Kabbalah by… forcing people to pronounce nonsensical syllables for hours on end in a sweatshop until something magical happens. It’s an absurdly plausible setup that allows Scott Alexander to do what he does best: make a bunch of esoteric Judaism puns.

Just like any great author of religious parable or speculative fiction, Alexander wraps his more stories in conclusions that are both foreseeable in hindsight and yet still completely, mind-blowingly unexpected. At times, it is reminiscent of a good Ted Chiang religion story, like “Tower of Babylon” or “Seventy-Two Letters”. However, the stories are bolstered by an understanding of how Alexander moves through the world, always trying to shake down the world for answers.

III: The Art of the Tale

Scott Alexander often reminds me of

, a literary critic on Substack who has written at length about the declining health of prestige publishing in general and literary magazines in particular. One of her recurring ideas is that the short story form itself is not as viable as it once was. Of the short story, she writes:Traditional short stories tend to lack an awareness of the reader as a living presence. That's because these stories insist quite strongly on the reader's complete and immediate commitment.

The reader needs to enter fully into a traditional story, giving over their consciousness to this living dream. And that's something the reader will only do if: a) they already trust the writer; or b) they trust the magazine or journal's judgement enough that they're willing to consider the possibility that a story might be worthwhile, just because it happens to be published in this place.

—Naomi Kanakia, “On Mars, everyone truly finds their level”

Kanakia has expressed doubt that the short story form can thrive at all in an era of divided attention spans sand low institutional trust. So what’s the answer? Kanakia’s response to the short story is the tale, a form that appears on her Substack weekly:

My stories are different from traditional fiction in that they don't make an overt, immediate demand that you believe in the reality of this fiction. You're not inhabiting this tale; you're just being told about it.

But there's a way in which the tale's breeziness also makes it more realistic. That's the magic. You don't actually need to describe the red rocks and the soaring vistas of Olympus Mons. That's not how you put us on Mars. Instead you put us there by just... assuming that's where we are! Write to us just as easily as you would if we were all on Mars together, talking about current events.

When I describe the tale format to people, sometimes they get defensive. Oh, I want to write things that demand the reader’s full, unyielding attention. Okay… but that insistence that the reader enter fully into the fictional dream is somewhat unrealistic, because readers don’t want to give their full attention to something unless they know it’s good. This means that if something that’s impenetrable except to someone’s full attention then people won’t read it, and nobody will ever know that it’s worth reading.

—Naomi Kanakia, “On Mars, everyone truly finds their level”

These tales may lack the immersion of a short story, but even moreso they lack the expectation of immersion. Kanakia’s stories are fictional, but they aren’t declared as such at the outset. You don’t say to yourself, “I’m reading a short story… time to lock in,” when the story begins. More often you suddenly realize that you’ve been “tricked” into reading a short story five minutes in!

Scott Alexander’s fiction works in a similar way. While it appears with the delightfully nerdy label epistemic status2: fiction, it can still momentarily pass as nonfiction due to the typical content on his blog. This ambiguity can be used to great effect, as some of his stories closely mirror real life. One tale begins like so:

Thanks for letting me put my story on your blog. Mainstream media is crap and no one would have believed me anyway.

This starts in September 2017. I was working for a small online ad startup. You know the ads on Facebook and Twitter? We tell companies how to get them the most clicks. This startup – I won’t tell you the name – was going to add deep learning, because investors will throw money at anything that uses the words “deep learning”. We train a network to predict how many upvotes something will get on Reddit. Then we ask it how many likes different ads would get. Then we use whatever ad would get the most likes. This guy (who is not me) explains it better. Why Reddit? Because the upvotes and downvotes are simpler than all the different Facebook reacts, plus the subreddits allow demographic targeting, plus there’s an archive of 1.7 billion Reddit comments you can download for training data. We trained a network to predict upvotes of Reddit posts based on their titles.

—Scott Alexander, “Sort By Controversial”

The extra frame-breaking statement at the top is a final flourish that can keep people asking if it’s true even after the tale ends. When a story doesn’t demand a particular submissive state of mind, the author has more freedom to create different sorts of reading experience. It can hit your brain in different ways, directly or obliquely.

Instead of asking the reader to submit to a distinct experience, Alexander and Kanakia provide an in-between frame that feels more continuous with the rest of their project. The tales are not differentiated and announced by a Table of Contents. They work fine as standalone stories, but they also provide a different way to get some idea across. In the end, this gives them much more vitality than they would have on their own.

Scott Alexander and Speculative Fiction’s Future

I’d like to return to this broader point about short stories and institutional trust. I would guess that Alexander’s short stories have reached tens of thousands of people who would never touch “prestige literature”. They read these stories because they trust their author as an honest truth-seeker and tastemaker, much as they might have treated our publishing institutions a century ago.

Alexander’s stories are successful in part because his “tales” ask less of the reader, but they also benefit from a great deal of trust in Alexander himself. Alexander operates as both editor and author of his own outlet (something not really possible in the past), so his reputation becomes that much more important. And Alexander commands rare respect in the ideologically-fractured circles that he operates in.

That aforementioned Quillette article describes Slate Star Codex as a “parallel literary institution”, which is very much in keeping with these themes. For many readers, Slate Star Codex was not just a blog, but a space where Enlightenment values flourished after stagnating in the institutional world. If Alexander’s nonfiction derives vitality from a lack of institutional trust, then it makes sense that his short fiction would also have unique life.

This isn’t to say that the establishment has been ignoring Scott Alexander, despite his best efforts. He hasn’t published a collection on the literary circuit or gone through the usual motions of an aspiring writer of fiction. Considering his actions up until now, he’s probably happier that way.

Scott Alexander could certainly become a famous fiction writer if he tried. But I’d like to believe that a healthier literary ecosystem would recognize the fiction of someone as well-known as Scott Alexander whether he pushed for it or not. Scott Alexander’s work may be meta, online, and weird, but Moby-Dick and Infinite Jest were pretty weird too. Perhaps the perceived “weirdness” of Alexander’s output says more about the state of our current literary institutions than anything else.

I have written before on how speculative fiction institutions currently fail to engage with fiction’s digital cutting edge. Despite technically being “web fiction”, the online magazine economy lacks a certain vitality that can be found in blogs like Alexander’s and Internet message boards. Just as traditional music and video institutions had to learn from streaming to survive, traditional literary institutions may have to look to authors like Alexander to remain culturally relevant.

Any speculation about the future of speculative fiction will include some prediction of its form, intentional or otherwise. It is only natural to predict more of the same, but we cannot assume that the “magazine short story” we know today will continue to be the defining unit of speculative fiction. The only way to imagine an alternative is to pay attention to less conventional authors, and specifically ones who are prototyping new models of what speculative fiction can be.

The closest magazine equivalent is Nebula nominee “Utopia, LOL?” by Jamie Wahls, an author who unsurprisingly frequents similar parts of the Internet.

“Epistemic status” is essentially a way to declare your level of confidence in own argument (with the earnest expectation that you might be proven wrong)

This is great! Got me going back through some of Scott's old fiction.

One of my favorite series is the Bay Area House Party posts. I just happened to take my own stab at that formula, posted to the Hidden Open Thread yesterday

https://nicoroman.substack.com/p/ancient-fragment-of-a-bay-area-house

I loved this essay.

One pedantic correction—the departure point for UNSONG is Apollo 8, the first mission to orbit the moon. It's based on the idea that the moon projects from the interior of a sphere, so when you try to go around the moon, you end up cracking the sphere.