'Primer' and the Existential Horror of the Granger Incident

WARNING: SPOILERS FOR PRIMER & BACK TO THE FUTURE

This topic was suggested by one of our founding members. If you’d like to submit an idea for a story every season, sign up for a founding membership today!

Most films that employ time travel use it to spin some grand romantic narrative: think Back to the Future (1985) or Avengers: Endgame (2019). These films generally gloss over time travel’s most unsettling implications— even when a time paradox initiates Marty McFly’s physical disintegration, it all turns out okay. But in Primer (2004), time travel is not romantic at all. It is a blunt instrument that creates unspeakable horrors.

Primer is an indie film about Abe and Aaron, two ambitious engineers who are testing out their latest startup idea in the garage. While their so-called “Box” was designed for superconductivity, Abe and Aaron soon discover that it has mysterious temporal properties. Even though Abe and Aaron are both as cautious as we could expect them to be, their time travel experiments quickly spiral out of control.

Primer succeeds conceptually because it resolves the famous grandfather paradox— the contradiction that arises when a time traveller goes back in time and kills their own grandfather in his youth. If the time traveller’s grandfather died before giving birth, wouldn’t the time traveller never have been born? But if the time traveller had never been born, wouldn’t they have been unable to kill their grandfather in the first place? Either way, the situation has reached a logical impasse.

But in Primer, characters can only travel back to the point at which they turned on the Box. Since they cannot time travel back to a point before the start of their journey, they also cannot prevent themselves from time traveling in the first place. Paradox averted! See the chart below for a visual explanation:

As Scott Meslow writes in The Atlantic, time travel struggled on the big screen until directors learned to shift their focus. Mainstream audiences watch time travel for the fun and romance of escaping fate, not the intricacies of time travel mechanics. Truly consistent time travel— seen in stories like Robert Heinlein’s “All You Zombies”— asks a lot of the audience. The convenient time travel that we see in movies today is riddled with holes that we are simply not supposed to investigate.

Take Marty McFly’s aforementioned physical disintegration. If Marty McFly really caused a timeline change that disrupted his own existence (like he did in the film), he would simply disappear all at once, not vanish one limb at a time. And if we want to get really technical, not even the film’s resolution would preserve Marty’s existence.

Because would Marty’s parents really have conceived on the exact same date as they did in the original timeline? Would his mother really have given birth on the exact same day? Would the exact same sperm really have been first to the egg? No, in all likelihood our hero would be forced to confront some alternate Marty upon returning to the present. But we’re not supposed to think about that!

This is not a flaw of the film; it is an editorial choice. Back to the Future sacrificed coherence for the sake of accessibility. In exchange, it can afford to be easier on its audience. The audience can just turn their brain off and enjoy some lighthearted fun.

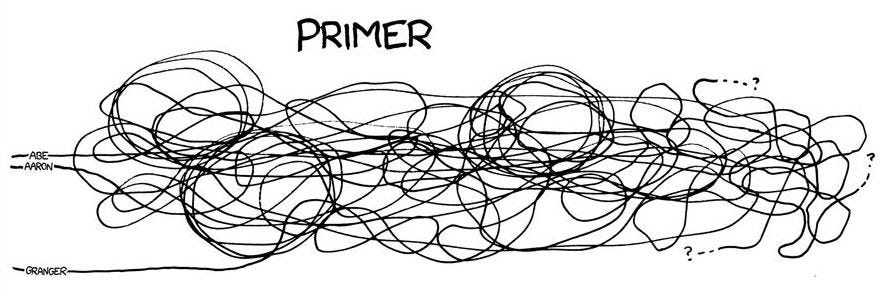

But incoherence also limits a story’s options. If a story has a shaky foundation, only so much is possible before its limitations are laid bare. But if a story has a strong foundation, serious complexity becomes possible. And this is where Primer comes in. Perhaps the best illustration of Primer’s complexity is this relevant xkcd:

While Primer starts off slow, its dry engineering jargon gives way to a reality that is rapidly spiraling out of the protagonists’ control. Abe and Aaron start bleeding from strange places. Mysterious figures start appearing. Confusing sounds go unexplained.

These near-paranormal events clash with the film’s austere, realistic setting to create an atmosphere that is extremely unsettling. Primer was limited by its truly shoestring budget of $7,000, but this ended up complementing the horror of the film. If Primer had Hollywood-caliber editing and gloss, it wouldn’t feel as real.

At a certain point in the film, Abe and Aaron decide to get back at their old business partner Platt by punching him in the face. They figure that if they time travel back after the fact, then they’ll be able to enjoy the experience with no consequences. But en route to their destination, they see their acquaintance Granger approaching them in the rearview mirror. After confirming Granger’s current whereabouts, they should decide that he should not be there. So does that mean he is a double? In that case…

The horror of the situation sets in when they realize that this is a new Granger who has been sent back by their future selves, which they would NEVER do unless there was an absolute emergency in the future. Abe and Aaron have an emergency meeting and rack their brains for any situation in which they would actually tell Granger about the Box. But the only answers they can come up with are catastrophic. Something is terribly wrong. Something is terribly wrong. Something is—1

The scariest horror films rarely show their villains on screen— what you can’t see is infinitely scarier than what you can. But the Granger Incident takes this a step further by hiding not only the villain, but also whether or not they even exist. Could Platt be responsible for this impending catastrophe? Aaron? Abe? Someone else? Or is there no villain at all? Maybe the fraying of reality has simply accelerated beyond any one person’s control. We can only guess; all we get to see as viewers is the resulting chaos.

But even much of the chaos described in the film happens off screen, forcing viewers to put together the pieces. Primer never shows what sparked the Granger Incident. It never shows Aaron fighting with his doubles. It never shows the original events of the ill-fated party that drives much of the action in the film.

Because of this, it’s difficult to make meaning out of Primer even after it comes to a “resolution”. Loose ends may be resolved, but most of those loose ends were never even made clear to the audience in the first place. And a careful viewer may shudder after realizing just how many loose ends may remain.

When we watch a time travel film, we generally expect to be reassured in some way. Back to the Future reassures us that minor positive changes can entirely reshape our lives. Avengers: Endgame reassures us that things are darkest before the dawn. Even grittier time travel films like Looper (2012) bring hope to a future clouded by darkness.

But Primer just comes in to our mundane reality and gives it a little shake. We leave feeling confused, uneasy, disoriented. It’s difficult to feel reassured about anything at all. What happened? Did the protagonists succeed? What does success even look like? What would success even mean?

When I first saw Primer, I had learned to treat time travel films like fireworks. They dazzle you with their expensive effects and romantic plots, but their beauty depends on viewing them from a comfortable distance. I had learned to let myself be swept along for the ride and only ask questions later.

So I originally found the drab atmosphere of Primer off-putting. Not only does it look mundane, but even its complexity is understated. The film really does not give the viewer much without a concerted effort to figure it out. By the end of the experience, I felt a bit cheated. I knew to expect a confusing film, but I didn’t think the confusion would be so… beige.

But after turning it over in my head amid multiple rewatches, I learned to treat Primer more like a snowflake. It has a rough exterior that is not immediately appealing. But upon closer inspection, its beauty shines through— in all its disturbing complexity.

Primer may be dry and disorienting upon a first viewing, but that is simply the price of admission for all the future enjoyment that the film has in store. This post-viewing enjoyment has kept me coming back to the haunting world of Primer, again and again. If you’re willing to give it the benefit of the doubt, Primer will reward you with a truly unique experience that evolves alongside your understanding of the film.