Golden Age Science Fiction is Being Reborn... in China?

Part I of 'Why Chinese Science Fiction Feels Different'

Introduction

“The thing’s hollow—it goes on forever—and—oh my God!—it’s full of stars!”

—Arthur C. Clarke, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1941)

Golden Age SF from the 1940s and 50s has an unmistakable voice: tons of em dashes, workmanlike prose, and a use of exclamation points that feels rather quaint. Once the dominant mode of science fiction, Golden Age SF has since taken a backseat to a much more literary modern approach. While the literary quality of SF has certainly improved, many fans of SF still find the old style unique, nostalgic, and irreplaceable.

There are several narratives that explain the decline of Golden Age SF in America. Many younger SF fans would say that New Wave saved science fiction from an era of terrible prose and even worse politics. A typical rebuttal is “Golden Age for whom?”. Those who prefer Golden Age might lament that science fiction has become a mere branch of fantasy, losing much of the the technocratic rawness that made it special:

Both of these narratives attribute this change in science fiction to decisions made in literary circles (good and bad). But I would argue that this change in sci-fi was in many ways an inevitable consequence of America’s technological trajectory.

I understand why people hate the term, but I still think the term “Golden Age SF” has some usefulness— it captures not just a writing style but a certain optimism. Science fiction may be more inclusive, humanistic, and socially conscious today, but it is not exactly “golden” in terms of inspiring wide-eyed, pure awe of science.

Modern science fiction tends to view science through a lens that is more cautionary than awe-inspiring, exploring the horrors of surveillance states, industrial-scale dehumanization, and a world ravaged by the climate crisis. Even more hopeful stories are often framed in opposition to technological growth, more likely to celebrate a return to the natural state of the world than the triumph of human ingenuity.

Since these narratives still existed in Golden Age SF, it is tempting to think that this has always been the case. But Golden Age SF was more characterized by a romantic wonder that now seems quite old-fashioned. The broader America mindset too used to be much more in line with these stories, a quality that powered Golden Age SF just as much as the technological ideas themselves.

In the wake of the World Wars, the United States was the last Western country left relatively unscathed. The old guard of Europe looked on as America channeled its newfound economic might into an optimistic spirit, one that powered the greatest economic growth the world has ever seen. This of course also led to a flourishing of culture, including the birth of Golden Age SF.

This is why Golden Age SF is such a quintessentially American style. It required not just technical know-how and writing ability, but also a certain optimistic audacity about the future. Because of its advantageous postwar position, America was uniquely suited to pioneer the style. America plunged into new scientific and cultural domains with vigor, and the rest of the world followed.

This is no longer the case. America has not been laid low like Europe, but it is not the country of wide-eyed wonder that it once was. As revelations about industrialized food, surveillance technology, and nuclear accidents have come to light, America has become rather disenchanted with modernity. The new default is to view technological progress not with optimism and promise, but with skepticism and paranoia.

America may still control the primary organs of technological progress, and simple inertia will cause this to remain the case for a long while yet. But the world’s center of technological optimism is no longer in America. It’s in China.

Viewing Science as a Romantic Ideal

One day back at the station, Ah Quan asked an engineer about something that was troubling him. ‘In the sixties of the last century, humanity arrived on the moon. Why ever did we withdraw then? We still have not made it to Mars; we have not even returned to the Moon.’

The engineer was happy to explain. ‘Humans are practical animals; what was driven by idealism and faith in the middle of the last century could never last long.’

Ah Quan remained perplexed. ‘But are idealism and faith not good things?’

The engineer continued his elaboration. ‘I am not saying they are bad things, just that economic interests are better. If, starting in the sixties, humanity had spared no expense and fully engaged in the uneconomical venture of space travel, Earth would probably be much poorer now. You, I, and other ordinary people like us would never have made it into space, even if we have made it no further than low-Earth orbit. Friend, don’t take Hawking’s poison; he deals in things that we ordinary people should not toy with!’

The conversation changed Ah Quan. He continued to work as hard as he always worked, and on the surface his life remained as tranquil as ever, but it was also clear that he had begun to think about deeper things.

—Cixin Liu, “Sun of China”

“Sun of China” is a sentimental story about Ah Quan, a humble Chinese laborer who moves to the big city and ends up working on one of the massive scientific projects of his age. This project is the China Sun, a satellite that will redirect the sun’s rays for projects that will benefit all mankind. The story is full of unbridled, sincere awe towards the promise of modernity in general and modern science in particular.

In an American context, such a storyline would have to develop complications. Maybe the China Sun is the product of industrialized child labor. Maybe the China Sun ends up exacerbating the climate crisis. Maybe the China Sun was spearheaded by some oligarch to sanitize his image. The typical American readers will imagine any number waiting for the other shoe to drop. But as it turns out, the China Sun is just straightforwardly good.

Cixin Liu, the author of “Sun of China”, conveys in his fiction a great deal of faith in the transformative power of science. Similar to his Golden Age forebears, Liu portrays science as a tool that is not just instrumentally useful, but also a worthy end unto itself. The draw of scientific wonder need not be grounded in anything practical or material. After all, “are idealism and faith not good things”?

Many genre writers were very tired of this scientific idealism by the end of the Golden Age, having read enough various riffs on the awesome power of scientific knowledge to last a lifetime. This dissatisfaction led directly to New Wave, which is understandable. There should be an impulse to shine a light on the blind spots of this philosophy when the topic is relatively unexplored.

But expectations have changed so much that the original idealism has become the refreshing perspective. On a recent podcast episode,

compared Chinese SF to Game of Thrones in that both bring expectations closer to baseline. We’re conditioned to expect our fantasy heroes to be saved by plot armor and our sci-fi technology to produce unexpected horrors. But Game of Thrones makes you read fantasy and think, “huh, maybe this character will actually die”. Similarly, Chinese SF makes you read sci-fi and think, “huh, maybe this technology will actually just be good”.So why did expectations change so drastically? In the end, this had less to do with the literary realm and more to do with broader trends in the culture at large.

How American Science Lost Its Luster

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

—Carl Sagan, “A Pale Blue Dot”

The 1960s were a Golden Age for science fiction, but they were arguably even more of a Golden Age for science in general. The Space Race was in full swing. The GI Bill had just created a whole new class of Americans with STEM degrees. Demand for science content shot through the roof, and a unique scientific spirit took hold that bordered on religious at times.

For me, the quintessential expression of this spirit is the “Pale Blue Dot” monologue by Carl Sagan during his wildly popular PBS series Cosmos. He frames science as a way to not just understand the world but also bring greater mutual understanding. In Sagan’s world, science is a beacon that allows us to ascend above petty quarrels and view each other as fellow human beings. Cosmos came out a little bit after the Golden Age (1980), but it can be seen as a capstone to the scientific fervor of the era: its 500M strong audience shows just how receptive people were to this message.

But trust in American institutions has been plummeting for decades, and American life feels more fractured than ever. Science as an institution has been particularly hard-hit, with a large chunk of the American population completely turning their backs on the scientific mainstream. In just a few years, the government has gone from staffing our scientific institutions with highly-credentialed professionals to ideologues who oppose the scientific consensus on matters like vaccines and the cause of AIDS.

The climate crisis was particularly damaging for the reputation of science, shattering the myth that it could completely transcend more petty human concerns like politics. Once science was dragged into the political arena, it lost the unifying mystique that it had once held. At the same time, the US is in the process of educational backsliding, with most areas of STEM performance declining since 2008.

Popular science institutions have been losing steam as a result, with mainstays like Popular Science and Discovery Channel facing an uncertain future. Communication channels for science still exist, but they haven’t been able to create the same spark that powered the idealism of the 1960s. Even Cosmos itself was rebooted to critical acclaim in 2014, but sleek production value wasn’t enough to make it even half as impactful as the original.

But across the Pacific, popular science is going through a new boom. China is now in the early stages of America’s mid-century trajectory, with a whole new class of highly-educated people hungry for scientific knowledge. They also have the advantage of the Internet, which has made science even more accessible than it was then.

China is not immune to 21st century problems, but its institutions appear to be in a far healthier state. It is difficult to get an accurate picture, but a higher degree of trust seems to be apparent anecdotally and shown in the numbers. The fractious nature of American society is often cited by the CCP as evidence that sacrificing autonomy for the sake of harmony is the right approach.

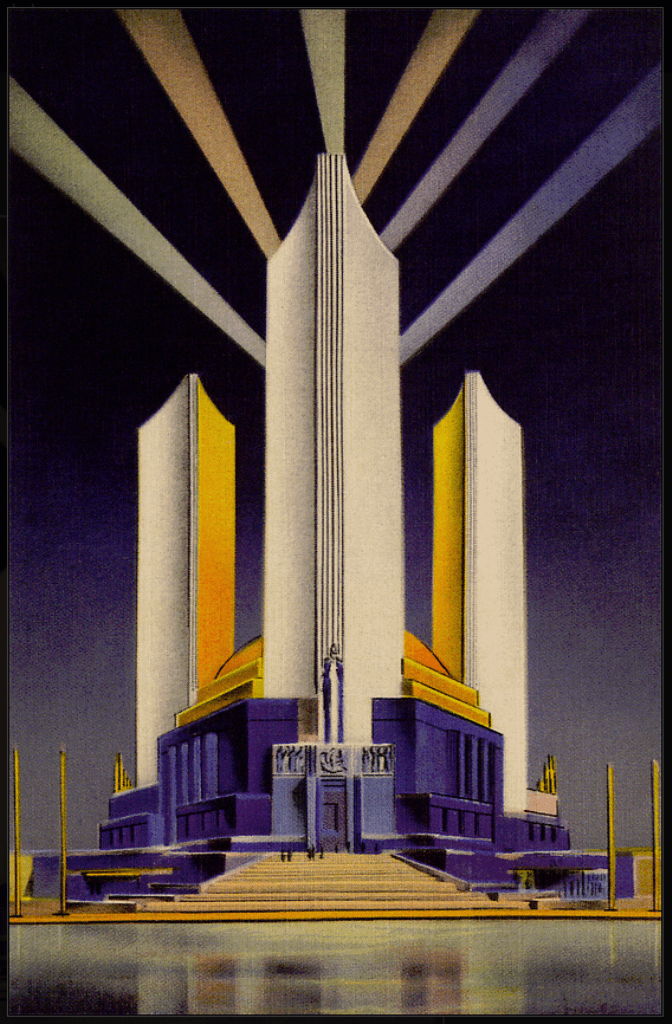

Chinese citizens are also better positioned to enjoy the current fruits of technology in their day-to-day. Most American cities were built in the mid-century, which can feel antiquated to Chinese tourists used to modern infrastructure. Meanwhile, almost all of the major Chinese downtown cores have sprung up in recent decades, and the difference can really be felt in the physical landscape (see below). All of this creates much better conditions for an idealistic view of science to thrive.

Science Fiction or Science Fiction?

A piece of science fiction writing may be good fiction and yet bad science fiction.

There is an extra ingredient required by science fiction that makes literary and dramatic virtue not entirely sufficient. There must, in addition, be some indication that the writer knows science.

—Isaac Asimov

There has been a mild but noticeable shift away from the term “science fiction” in genre circles. While most fans use terms like “SFF” or “speculative fiction” to cover a broader range of works, many writers use them to actively distance themselves from the science fiction label. Margaret Atwood, a persistent critic of science fiction, once dismissively wrote, “Speculative fiction encompasses that which we could actually do. Sci-fi is that which we’re probably not going to see.”.

This would all seem quite odd to Golden Age SF authors, who often viewed their work more as an extension of science than literature. Golden Age writers like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were overt about wanting their stories to enlighten people about real science. Asimov in particular was quite accomplished as a science communicator, writing books like The Intelligent Man’s Guide to Science. Their writings were intended more as demonstrations than aesthetic accomplishments.

Today, labeling a story as a “demonstration” like this seems insulting. It doesn’t sound very glamorous or aspirational. But not too long ago, scientific demonstrations were aspirational. Carl Sagan, Don Herbert, and Richard Feynman were role models just as much as the authors of their day, creating a sort of artistry out of truth rather than literary aesthetics.

Most modern sci-fi authors don’t have such high-minded ideals about the purpose of their work; they care more about just telling good stories. Someone holding Asimov’s views would likely face a chilly reception. The conservative pro-Golden Age narrative is that this is because writers and publishers stopped caring as much about science, in service of pushing a “woke agenda”, or something like that.

But this narrative fails to grapple with just how much science has fallen in prestige. The simplest explanation for there being less science in science fiction now is that there is just a lot less enthusiasm for science now in general.

But again, things are different in China. We’ve already talked increasing interest in popular science, but the biggest difference between American and Chinese science fiction is the shape of their respective sci-fi institutions.

Despite being less well-known internationally than its American counterparts, the Chinese sci-fi magazine Science Fiction World may have a higher circulation than all of the American magazines combined. SFW has declined a bit since its peak, but it’s as healthy as anyone could expect from a magazine in 2025. Meanwhile, many classic American sci-fi magazines like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction have fallen on hard times, with the entire industry in a bit of a precarious position (see below).

With that being said, science fiction is probably still more popular in America than China, at least in terms of mainstream recognition. But sci-fi magazines have always been the most generative part of the scene, so their health has disproportionate weight. American sci-fi magazines are more of a thing you have to actively seek out, whereas the popularity of Science Fiction World means that prospective young writers are more readily pulled right into the center of the genre. The current situations suggests that Chinese science fiction has a relatively dynamic future ahead.

Perhaps even more significant is the fact that Science Fiction World mainly targets high schoolers and college students, even publishing a themed issue based on the gaokao entrance exams. The “Bus Theory” of Chinese sci-fi1 posits that most fans leave sci-fi upon graduating to pursue more “adult” endeavors. As a result, the beating heart of Chinese sci-fi is inside the high schools and the universities. Meanwhile, American science fiction institutions are still largely made up people from a previous generation.

In the 1960s, the United States too had impressive university engagement with science fiction. High-visibility clubs like the SF&F Society at Michigan State and the Chimera Club at North Carolina were common, with some even hosting their own conventions. But such clubs have largely died out. Just 12 of the top 50 public universities in the US have any kind of science fiction club at all.2 Neither MSU nor UNC are to be found in those 12. There are exceptions, like Texas A&M sci-fi bastion Cepheid Variable, but even these clubs tend to be much further away from core sci-fi institutions.

This state of affairs has its tradeoffs, but one benefit of having sci-fi and academic institutions under one roof is that it pushes science fiction closer to the frontiers of science. Academic institutions are always doing groundbreaking research, which can be difficult to stay on top of from the outside. If sci-fi activity is coming out of the universities, then not only will STEM students be closer to sci-fi, but sci-fi will also have more proximity to new scientific ideas.

When sci-fi had closer proximity to academic and scientific institutions in America, the genre seemed to be far, far ahead of the times. These stories were not 5-10 years ahead, but 50 or 100— so much so that they continue to make great adaptations today! Authors like Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke were able to forecast AI ethics, AirPods, and communication satellites. Ultimately, Golden Age SF was able to compensate for many of its literary shortcomings with its greater predictive power.

As science fiction continues to expand across the university scene in China, there may in fact be a true rebirth of Golden Age SF. On some level this makes me sad, because I like the idea of America as the center of scientific idealism. But if scientific idealism is on the way out regardless, I am at least glad to see another nation pick up the torch.

Conclusion

No one would know how far the China Sun would fly, and what strange and wonderful worlds Ah Quan and his crew would behold. Perhaps one day they would send a message to Earth, calling them all to new worlds. Even if they did, any response take thousands of years to arrive.

But no matter what happened, Ah Quan would always hold to his parents living in a country called China. He would hold to that small village in the dry west of that country.

And he would hold to the small road of that village, the road on which his journey had begun.

—Cixin Liu, “Sun of China”

The United States has experienced the fruits of modern science for so long that it can be easy to take all this for granted. We are now at the other end of the spectrum, when we have so much distance from diseases like diphtheria that people may presume that vaccines are no longer necessary.

But stories like “Sun of China” can remind us of just how far we’ve come. Ah Quan went from agricultural laborer in rural China to high-flying window cleaner in post-Industrial Beijing, which gave him the perfect skillset to wipe down giant mirrors among the stars. Anyone with Ah Quan’s life experience would find it hard to view modern science with anything other than pure awe.

Right now, Chinese SF isn’t exactly known for overturning existing paradigms. Cixin Liu names Arthur C. Clarke as his biggest influence, and most of the beats of Chinese SF will feel familiar to Golden Age SF readers. But that doesn’t mean that Chinese SF has nothing to teach us. Rather than seeing Chinese SF as merely “pre-New Wave” or “backwards”, we can see it as a form of rediscovery, a reminder of that original sense of optimism about science that created sci-fi in the first place.

Science can sometimes just be good. It’s not a particularly strong statement, but it’s a sentiment that our culture should take to heart.

Author’s Note

It has been hard for me to articulate what I find dissatisfying about modern science fiction. On the one hand, sure, I wish that science fiction had a more scientific focus. But I’d also take a story by Caroline M. Yoachim or Carrie Vaughan over a story by Isaac Asimov any day of the week. The stories that have come out since 1970 have mostly been better stories. So I don’t think this preference fully explains why I find the modern science fiction landscape lacking.

But I think I was finally able to articulate it in this post. Science fiction’s lack of technological speculation isn’t just about a shift in literary sensibilities; it is also about a loss of optimism and vigor in the zeitgeist. People are still pretty good at speculating about new ways that our apparently inevitable digital hellworld will be horrible! But I feel a sense of loss when I read sci-fi from a time when people felt more able to speculate about the promise of technology and the possibility of a better world.

Shortly before her death, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote about the importance of imagining new futures in art that transcend the pervasive fears of our modern society. There has been some much-needed recent movement in this direction— genres like solarpunk and hopepunk bring a refreshing optimism to a genre that has been dominated by dystopia for so long. But even so, many of these stories seem to have very little faith in science! Efforts to tame nature are often seen as something to be overcome, and many stories even depict Earth as being better off post-humanity, allowing alien or robots to clean up the ashes of humanity’s technological hubris.

I like Chinese science fiction because it seems like authors don’t feel obligated to explain themselves in the same way. In “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”, Le Guin calls the reader out for not believing that a world like Omelas could be possible unless there was some internal darkness. I feel like this extends to science fiction somewhat— scientific innovation in sci-fi doesn’t feel “complete” unless there is some reckoning with unforeseen consequences. But in Golden Age-style SF, this obligation doesn’t feel nearly as pronounced.

This isn’t to say that Golden Age SF and Chinese science fiction don’t consider the negative consequences of technology; there is still much disaster borne out of technological hubris. But there is also space for stories like “Sun of China” and “The Rocket”: science can just be good, no further explanation needed. In today’s world, it’s nice to live in a story with that feeling.

This essay covers less than a third of what I originally had planned, so you can expect a lot more writing about Chinese science fiction in the future. But until then, thanks for reading! And many thanks to , , and for boosting our last couple posts! We really appreciate it! :)

—K

I don’t have a proper source for this theory, but Regina Kanyu Wang mentioned it to us on the podcast so I’m just taking her word for it that it exists.

It’s hard to be exact about this, but I was using the USNews Top 50 rankings, and the existing sci-fi clubs that I found were as follows:

Cepheid Variable at Texas A&M

Skiffy at William and Mary

Enigma at UCLA

Darkstar at UCSD

SFFWWB at UC Berkeley

Intergalactic at OSU

SF Society at UMass Amherst

SF4M at Stony Brook

SLUG Sci-Fi at UC Santa Cruz

Woman and Tech SF at Indiana

Fellowship of the Page at UConn

Board Game Underground at UC Boulder, a club that actually changed its name from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Underground (SFFU) to Board Games Underground (BGU). Sign of the times?

UNCG is not a Top 50 school, and our club SF^3 has only put on one StellarCon since I've been there (not this year). It still exists, but it's insular. https://linktr.ee/stellarcon.nc

What I'm seeing is that fantasy is way more popular than science fiction. Every one of the critters my Alien Ecosystems came up with had magic powers, and most of them were labeled 'good' or 'evil'. We had a whole discussion about amoral evolved biological creatures, just trying to feed their babies however they can, vs created cultural monsters that exist solely to be killed by heroes. They were just more interested in monsters.

As an educator and SF author myself I am very definitely interested in science as a way of life. But I am in the minority. Most of the authors I meet at cons were English majors.