The Future of Fantasy is Sakug(AI)

How GenAI might transform fantasy literature without destroying the human element

This post was partially inspired by ‘s “Prepping for the Editor G*ds”.

NaNoWriMo’s recent shutdown foreshadows many ugly battles on the horizon over the future of writing and AI. Most public-facing creatives argue that no machine will ever to be able to replace the unique voice of a human author. But many business and tech leaders assert the exact opposite: given the rapid rate of improvement, most writers will soon be entirely replaced by AI that can do the job faster and better.

But neither group spends much time outlining what they want their ideal AI future to look like. Do writers actually expect people to close ranks and block AI tools out of the goodness of their hearts? Certainly some will refuse AI art on ethical grounds, but the growing list of reasons to abandon Big Tech hasn’t stopped the vast majority of people from continuing to use their products. If writers didn’t think that AI was ever capable of producing successful writing, then they could simply laugh it off (as they would have done a decade ago). The fact that they don’t speaks volumes.

Similarly, why do business types think that people will actually want to read books generated by AI? If someone is drawn to literature over more dopaminergic forms of entertainment, then they are probably also someone who cares more about intentional craftsmanship, true novelty, and the creative process. Not to mention the fact that they probably already dislike the idea of AI art itself! There has already been such a strong backlash to the idea that it is hard to imagine AI-generated art ever going over well with the reading public.

People will use AI tools, whether writers like it or not. People will continue to buy art from human writers, despite the lofty claims of mechanistic businessmen. The real question is this: what will the job of an author look like in a post-AI world?

In fantasy, authors may be able to draw inspiration from the concept of sakuga.

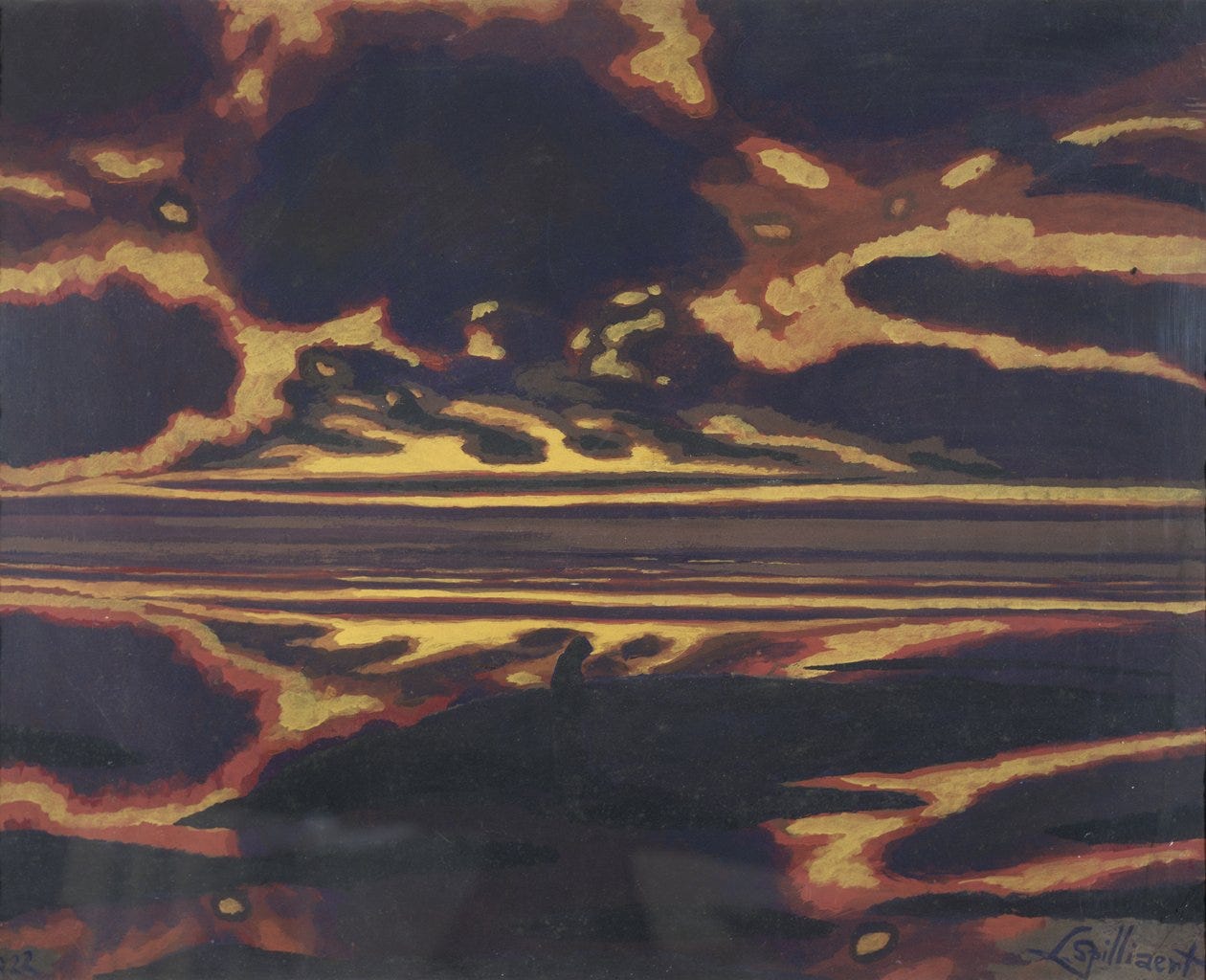

The tight schedules of Japanese animation make it impossible for an animation studio to pour maximum detail into every single frame. As a result, most studios cut corners on less important scenes in order to save resources for the artistic, climactic scenes that matter most. These scenes are called sakuga.

In most cases, the important frames in a sakuga sequence are drawn by a master “key animator”, which gives the scene a more explicit artistic direction. Character designs and sets will obviously retain common visual elements throughout a show, but a great key animator can take these designs to the next level and elevate them to true art.

The sakuga model works well for most animated shows, since viewers tend to focus on things other than animation. They will focus instead on the characters and the story, only turning to the animation during flashy fight scenes that anchor the action. These epic climaxes are what really stick in viewers’ minds, so it makes sense for studios to allocate a disproportionate amount of resources to them.

The same holds true for many fantasy novels. We can draw a rough analogy between animation and prose, both being the medium through which the story is told. Most fantasy readers similarly focus their attention on the characters and the story, only focusing on the prose during epic climaxes. But fantasy writers do not have the luxury of outsourcing the more functional parts of their books in the way that key animators do. For the most part, authors just have to do it themselves.

Until now. AI may not be able to produce great prose yet, but today’s LLM technology is already able to produce serviceable prose. With the right approach, an author with technical know-how could train an AI to emulate their style. The goal would be not to completely outsource the creative process, but to free the author up to focus on the core ingredients of their art. In other words, they could focus on their “sakuga”.

Assuming AI fantasy writing can reach some base level of quality, this concept already a lot of obvious potential. A slow writer with an intricate world could focus more of his attention on figuring out the lore rather than figuring out how to channel that lore through conversations that feel rather contrived. Perhaps GRRM would be on his third series in the Game of Thrones universe by now if he had just been able to plug all the Westeros lore into an LLM and focus on dialing in for the most critical passages.

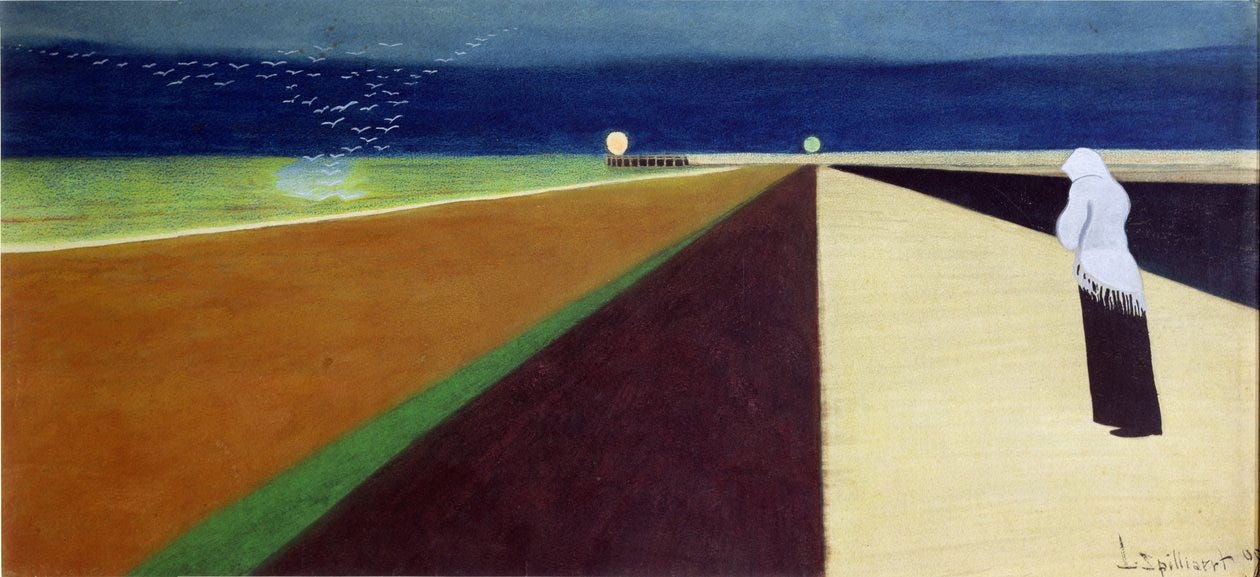

In this world, creatives could still use their humanity to set their work apart. Rather than a binary AI v. no AI classification, books could be categorized based on the % of sakuga in the text. Most clothing items on the market are mass-produced, but there is still a market for handcrafted artisan goods. By the same token, high-end booksellers might only carry “75%+ sakuga” fantasy as a point of pride. Perhaps the proliferation of GenAI text would even elevate readers’ standards for craft.

These outcomes are already pretty interesting on its own, but the sakugAI concept might also have potential to reshape the textual medium itself. How does this concept transform the fantasy novel if taken to its natural conclusion?

Since generative AI produces writing near-instantaneously, it could generate not just one but multiple versions of each book with relative ease. And this opens up a whole new world of possibilities. What if fantasy novels had no single authoritative version? Novels could be not one body of text, but a family of texts connected by their shared sakuga nodes. The core elements would remain the same, but the in-between scenes would be different and personalized to the reader.

For example, let’s say that Jenna loved Game of Thrones, but she found Brienne’s arc in A Feast for Crows exceedingly boring. Her personalized version of the text could have less Brienne and more Cersei in it, which could either be manually chosen by her or even determined by an algorithm that analyzes her past reading behavior. The story remains the same, but the emphasis differs. Minor events would get less attention in certain versions of the text, or perhaps no mention at all.

Ideally, the sakuga chapters and the in-betweens of a book would be delineated by visual cues. Perhaps the font would change, or perhaps the a pop-up would appear on the display. This would be an exciting event for the reader, a signal for them to fully lock in. It would also allow authors to reassert ownership over their work, showing how their 100% human output differs from mere AI writing emulating their style.

But most importantly, it would denote the sections of the text that are common to all readers. It would be quite difficult to discuss a book without knowing which sections others have also read!

Literature purists would obviously be disgusted by this notion on principle, so this approach is probably dead on arrival in the world of literary fiction. But the fantasy reader may not have these same qualms. Given that the core fantasy selling points— world, magic, plot— would still be human-made, “sakugAI fantasy” could have legs. And this raises interesting questions about the future of literature as entertainment.

In this brave new world of sakugAI fantasy, book discussion would be quite different. Readers would have to rethink the idea of “reading the same book”, as no two people would receive the same text. This less communal reading experience might repel some readers, especially in an already-atomized media landscape.

But it could also make some aspects of reading more monocultural. The same book could appeal to far more people, because it would be tuned to people’s preferences in the same way that music genres are now. Perhaps algorithmic technology could even get people to “read towards each other”, getting them outside of their comfort zones by peppering their in-betweens with tropes that they already love.

And these differences would give readers a whole new angle for discussion. Readers would inevitably trade notes, eagerly seeking out new lore hidden in their friend’s version of the text. It’s easy to imagine readers exchanging entire versions, debating the relative strengths and weaknesses of each: “Okay, your version of A Feast of Crows was pretty good, but have you read Jenna’s? Her algorithm was cooking!”.

This could create interesting trends on a larger scale, assuming some level of open-source / interoperability. Fans of celebrities could take their parasociality to the next level by acquiring Anya Taylor-Joy’s version of Harry Potter or Timothée Chalamet’s version of Dune. Readers could supercharge the sakuga chapters they love with the latest AI models or even combine them together. With the right marketing strategy, this could be a real racket.

Many writers see AI as an existential threat to the professional artist that may never be overcome. I don’t entirely disagree. Writing is a deeply human act, and it will be sad to see parts of this craft outsourced to the machines. But many crafts have been sidelined throughout history by the relentless march of technological progress. We still have many professional writers, but there are not nearly as many professional weavers, portrait artists, or calligraphers as there were in pre-industrial times.

This loss of virtuosity is tragic, and humanity is in some sense worse off for it. But none of these displacements killed off the art form itself, and we should not expect writing to be an exception. Many opportunities for writers will disappear, but new opportunities will present themselves as well. Fantasies with AI personalization could push literature back into the mainstream, bringing back sorely-needed capital that was gone years before GenAI arrived. And perhaps AI assistance could allow writers to better compete with the firehose of online content running all day, every day.

In a post-AI world, the role of the writer will have to change. They may become more of a tastemaker, an artisan, a specialist. Many creative communities will steadfastly oppose such changes no matter what form they take, so the first few innovators in this area will likely be ridiculed and hated. But in the long run, I don’t see a world where professional writers escape the consequences of this paradigm shift unscathed.

However, there is a big difference between willful ignorance and admitting defeat. Writers who believe AI will play a big role in the future of fiction should continue to pick their battles, not anticipate imminent irrelevance. They can and should seek fair compensation for AI model training, while at the same time try to envision how future art might preserve the human element. SakugAI fantasy is just one of many potential ways that authors could reassert their own uniquely human creativity. For the sake of artists everywhere, I hope it is just one of many more to come.