Dissonance and Danger in “The Princess and the Clock”

SPOILER WARNING: THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS FOR THE FILM INTERSTELLAR

If you are upset by narratives involving coercion / non-consent, please skip this article.

One of the best songs to come out of the pandemic years was "The Princess and the Clock" by Kero Kero Bonito. It has the sound of a video game, the themes of early quarantine, and the lyrics of an ancient myth. This union of future, present, and past became the common thread for KKB’s compilation album Civilization.

According to Kero Kero Bonito, the track "is the tale of a young explorer who is kidnapped while sailing the world, imprisoned at the top of a tower and worshipped as royalty by an isolated society. Trapped in her chamber, she spends years dreaming of escaping, until one day she disappears." Despite its heavy subject matter, “The Princess and the Clock” is a lush and hopeful track that is filled with the spirit of adventure.

While "The Princess is the Clock" is primarily about our fearless explorer's captivity in the tower, what has really stuck with me is her voyage and its untimely end. The more I reflected on that part of her story, the more her fate felt shockingly tragic. I've decided that this is because the song is soaked with themes of dissonance, which makes the themes feel much more visceral and real.

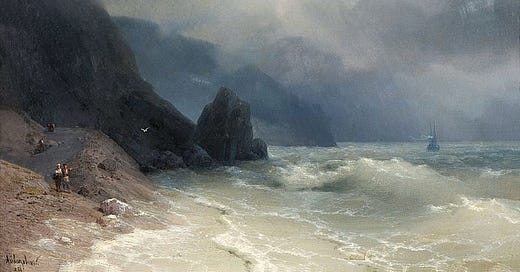

For starters, there's the dissonance caused by the freedom of the voyage and the captivity of the island. A princess sailing off into the open ocean clashes with our preconceived notions of how a princess is meant to be. A princess's role is fundamentally social: even adventurous Moana never travels without companions. The image of a princess who casts everything aside for adventure (even briefly) is surprising, compelling, and a little bit glorious.

But we have to remind ourselves that our “princess” wasn’t a princess at all. She only acquired this status after the islanders forced it upon her against her will. (I don’t want to keep referring to our unnamed explorer as “our unnamed explorer”, so from now on I’ll refer to her as Midori.)

So Midori goes from one of the freest roles in society to one of the most stifling— not just tied down physically, but also bound by an alien ceremonial role. This is such a dramatic reversal of status that you'd expect her to feel an even greater loss of freedom than an ordinary person.

So there's the dissonance between absolute freedom and absolute captivity. But there's also the dissonance caused by the profound danger of the sea and the comparatively mundane danger of a misguided cult.

We get uncomfortable seeing our heroes at the mercy of ordinary people. One vivid example comes from Interstellar, when Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) reaches Mann’s (Matt Damon) planet. After braving the dangers of space and city-sized waves, Cooper finds that his toughest challenge is actually Mann himself— a desperate man who planned an elaborate act of sabotage to save his own skin.

When we see Cooper at the mercy of mere Mann on those icy cliffs or picture Midori at the mercy of a strange cult on faraway shores, our first reaction is disbelief. Was this really all it took to bring our heroes to their knees? They braved the sublime only to end up at the mercy of the mundane. Their godlike qualities melt away as we remember that they are people just like you or me.

Then a different kind of fear sinks in as we recognize ordinary people as formidable in their own right, capable of rivaling something even as terrible as the sea. In the context of the sublime, we fear not Mother Nature’s malice, but her indifference. We may die a horrible death, but we can at least rest assured that our fate won’t be dictated by ill intention. On the other hand, humans are excellent at making each other's lives worse in new and exciting ways.

Midori's fate reminds me of an infamous Twitter poll: “would you rather be alone in the woods with a man or a bear?” This simple question sparked a conversation about gender, safety, and human nature after many, many women chose "bear". "Man or bear" has parallels to Midori's dangers: there's a similar juxtaposition of cunning human nature (island) with wild Mother Nature (sea).

For me, the most revealing aspect of "man or bear" was the discussion's focus. You might expect women who chose "man" to dwell on the concrete dangers of men; after all, men are capable of horrible acts that bears aren't even capable of understanding. But most answers were actually about betrayal. Women expressed more concern about a deceptively disarming man than a clearly dangerous man, and some even focused on people not believing them in the aftermath.

In keeping with the themes of "man or bear", "The Princess and the Clock" leaves room for a betrayal-oriented reading. The stanza about her capture reads:

Before she felt any fear

The air escaped into silence

She woke up lying on a gilded bed

With half a dozen maids around her

The most natural interpretation is that the islanders took Midori prisoner shortly after her arrival. But the ambiguity of "Before she felt any fear" leaves room for a longer interpretation of events. I doubt Midori would have gone down so easily if she got as far as that island. Especially since the island had such an obviously weird vibe!

I choose to imagine that the islanders earned Midori's trust. They buried her initial apprehension with warm hospitality. It had been a while since Midori had been around people, so the festivities reminded her of what she had been missing. After receiving a tour, Midori started to entertain the idea of staying. "Just stay for one night," they plead. "We've prepared a banquet!" they insist. Only after an entire day of buttering her up were the islanders able to spring their trap of betrayal.

Betrayal is so salient in part because our brains are poorly equipped to handle the dissonance involved. As social creatures, humans are wired to bond with others. So when a friendly person turns out to be an enemy, our cognition gets scrambled— not just because of the dissonance between our impression and their actions, but also because of the dissonance between our typically beneficial drive for connection and the harm it caused us.

It only takes one bad experience for something like "man or bear" or "island or sea" to surface those feelings of dissonance. When we find something "creepy" or "unsettling", it is not because it represents an imminent threat, but because it is hard to place. We know how to categorize the threat of a bear, but a man in the woods invites ambiguity. While there may be concrete concerns about a man in the woods, the question is closely linked to dissonance and a fear of the unknown.

In "The Princess and the Clock", the dissonance of betrayal is accentuated by other dissonance in the story: Midori just doesn't seem like someone who should be laid low by misguided islanders. Through their deceit, the islanders were able to steal not just Midori's freedom, but also one of her greatest assets: her ability to protect herself.

When I listen to "The Princess and the Clock", I remember that tragedies aren't always romantic or heroic. Sometimes terrible things happen without any real reason. As natural storytellers, this can be hard for humans to accept! But it serves as a good reminder of life's fragility—a narrative justification isn't enough to guarantee that something will last. Sometimes beautiful things just end, and we must not forget to show them our appreciation while they're still alive and kicking.

You can watch the video for "The Princess and the Clock" here.