Guest Post: "Art or Life?" by Isaac Olson

“Art or Life?”

Science, Art, and the Fallout of Throwing Soup at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers

Soup, Science, and Sunflowers

It’s easy to imagine Science and Art on opposite ends of life’s spectrum. The fields are often placed at odds, in everything from the education system to the job market. As an arts-minded oceanographer, I have always worried that my fields of interest would never truly intersect in the public consciousness.

And then, on October 14th, 2022, the worlds of science and art were brought hurtling together as messily as a can of soup splattered over a painting.

On that day, Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland, 2 members of the climate activist group Just Stop Oil (JSO), sparked outrage after they “threw soup on the Vincent van Gogh sunflower painting” in the National Gallery in London, glued themselves to the wall, and demanded the British government cease fossil fuel leases. Despite the painting itself sustaining no damage, critics were vocal in their condemnation. Online, the action was deemed “mindless destruction” that disrespected an invaluable piece of art. The activists were called “idiots” and “bullies,” with some Twitter commenters calling for “capital punishment.” While not going that far, in July 2024 Plummer and Holland were found guilty of “criminal damage.” Sentencing is expected in September.

What was often lost in headlines following the action was its justification. Most who heard about the protest wrote it off as a desperate attention-grab by a group with no care for artistry. Even fellow climate activists were hesitant to support the action due to this perception, especially before people realized the painting wasn’t damaged. But this interpretation ignores the activists’ admiration for van Gogh’s piece. Plummer reflected that “it’s a beautiful work of art” and commiserated with the “shock or horror or outrage” people felt when they saw something “beautiful and valuable” being damaged.” In reality, their admiration is what made the painting a target. Responding to the outrage, Plummer asked “where is that emotional response when it's our planet and our people that are being destroyed[?]”

That motive is at least comprehensible: If our society is willing to protect nature-based art, why is it not willing to protect the environment itself? If our society is willing to preserve future generations’ ability to enjoy an artistic rendering of nature, why not preserve their ability to experience nature? This hypocrisy is illogical, and so, the UK government should stop enabling the fossil fuel industry.

However, this reasoning was overshadowed due to misinterpretation over the action’s intended target. Many people assumed the activists were targeting artists or museums or oil paintings and felt indignant at the perceived harm to an innocent target. JSO explicitly called out the UK government, implying that politicians were the target. Realistically, JSO likely intended to garner public attention for their cause.

Regardless of intent, it’s certainly interesting to consider how much this action asked of the public. It asked us to reconsider our stance on the urgency of climate action and our involvement in a society solely permissive of actions that maintain the status quo. It asked us to recall how science tells us that Nature (and Art by extension) is facing an existential threat and emulated Nature’s destruction through faux destruction of an artistic rendering of Nature. Honestly, this is a difficult message to impart that relies on an understanding of the connection between Art, Nature, and Science that many aren’t primed for. Today, we often don’t consider ourselves within nature, and we see the art we create as divorced from the environment. And because humans and art are already separated from environmental science in the public consciousness, it is easy to draw a line between the people who care about art and society, and the disrespectful fanatics, rage-baiting to push their agenda.

JSO did itself no favors in explaining this dynamic. The protest relied on the apparent destruction of art in the name of science, a perception exacerbated by Plummer asking, “What is worth more, art or life?” Perhaps the dichotomy was meant to symbolize societal hypocrisy rather than personal beliefs, but to outsiders, it appeared antagonistic to artists. In fact, many people to this day hold lingering distaste for the action, being unaware the painting wasn’t damaged, and overall response to the action is mixed. A 2023 YouGov poll found 64% of respondents had a “somewhat” or “very” unfavorable view of JSO. The Annenberg Policy Center conducted a poll immediately after the action which found that 46% of respondents were less supportive of “efforts to address climate change” following nonviolent disruptive actions, compared to only 13% becoming more supportive. From these (limited) polls, it’s fair to argue that the action failed to overcome the dichotomous framing of its messaging, and was subsequently dismissed, even amongst the people it purported to engage.

But if anything could bring together artists and scientists, surely, it’s Nature, because artists and environmentalists share the same goal: to preserve and interpret life. Nature acts as a common ground, a balance of aesthetics and data, the source of the Arts and the foundation of science. And today, in an era of human-driven changes to the natural world, both scientific understanding and artistic endeavors are essential in protecting our environments. In fact, countless memorable environmental milestones have come from these disciplines acting in tandem, with Art and Science cooperating to allow us to better understand our world and our place in it.

Perhaps if this connection was more apparent in the public consciousness, people would have better understood the premise of JSO’s protest, and thus, would have been willing to question the hypocrisy in a society valuing art above the planet. At the very least, re-emphasizing this intersection could have lessened the messaging discontinuity that caused even other climate activists to dislike the action.

Thus, by emphasizing Art’s reliance on Nature, Nature’s reliance on Science, and Science’s reliance on Art, we can better recognize how both Art and Science are essential in preserving our ability to thrive within Nature. Through a renewed understanding of the intersection of Art and Science, we can reassert our relationship with Nature, and reconsider whether our society must be adjusted to forge a better world after all.

Art Relies on Nature

Nature is both the source and enabler of Art, providing the base ingredients out of which humans can create. The oldest human-created artwork is a 45,500-year-old cave painting depicting a pig – an image of Nature on Nature’s canvas, using, of course, naturally-sourced paint. Prior to the advent of synthetic pigments, colors were created exclusively from natural sources, such as rocks, bones, and minerals. Even today, some pigments remain prized because of their unique natural sources, including ultramarine (sourced from lapis lazuli or azurite), vermilion (sourced from cinnabar created by volcanic activity, and Tyrian purple (sourced from sea snail secretion).

Nature did more than provide painting materials - Nature was often a painter’s muse. From the idyllic landscapes of Roman antiquity to the pastoral grandeur of the Hudson River School, Nature was the supreme source of inspiration for countless artists. As a subject, Nature presented the chance for humans to redefine their connection to the environment. In the words of painter Thomas Cole in his “Essay on American Scenery,” “Nature has spread for us a rich and delightful banquet. Shall we turn from it? We are still in Eden; the wall that shuts us out of the garden is our own ignorance and folly.” Nearly 200 years later, it seems we were all too willing to turn from Nature. But in reconsidering the enduring artistry Nature has inspired, we can begin the process of revival.

Centuries before the American landscape inspired Thomas Cole, Indigenous peoples nurtured their reciprocal relationships with Nature into Art through cultural practices. Notably, many types of Indigenous art form dual purposes, providing both utilitarian and artistic value. Hopi ceramicists produce both sculptures and storage vessels. Pomo basketry is both a spiritual art and a necessity for gathering. Coast Salish Tribes continue to produce some of the most iconic Indigenous artforms, from preserving ancestry and culture through totem poles to enabling subsistence through canoe-carving. Such practices were essential to Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island and remain a source of cultural subsistence today.

Of course, art has had a similar lasting effect across many cultures. Consider how Nature was appreciated in both the odes of John Keats and the haikus of Bashō, how Christian hymns and Yoruba spirituals both honor the Earth’s majesty. All art is environmental, not simply in theme or emotion, but in essence. It has always been this way, and the erosion of this relationship has been accompanied by the erosion of Nature. Repairing this interdependence is a critical step to addressing the dissonance seemingly apparent in JSO’s action, and in understanding why there is no Art without Earth.

Nature Relies on Science

Science is undeniably essential in making informed decisions in a changing world, as it tells us what changes are happening and who is threatened, and how to respond. It also gives legitimacy to demands for change – just look at the influence of the statistic that 99% of scientists believe in human-caused global warming. Oftentimes, the Arts are essential in communicating science effectively. However, there is a history of Art being used to advance environmentalism without preserving facts, leading to misappropriated messaging, and even enhanced separation from Nature.

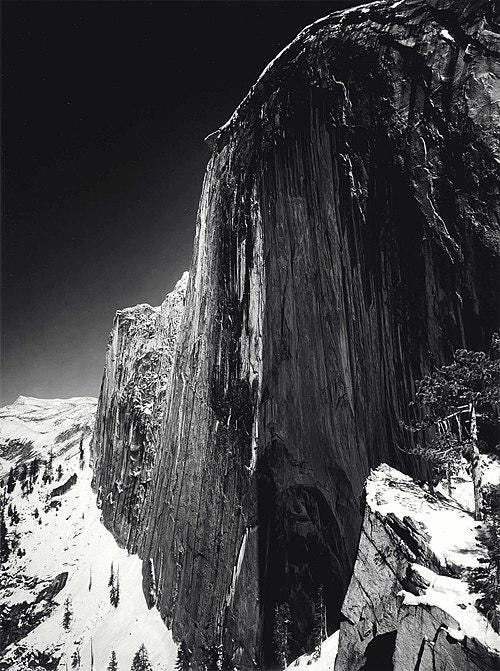

One example is the story of Ansel Adams and Yosemite. Adams made several visits to Yosemite beginning in 1916, and was personally touched by his experiences, saying that “[t]here are no words to convey the moods of those moments.” Pictures would have to suffice.

Adams’s hundreds of photos were so moving that they would be used to bolster an insidious agenda started years before: the erasure of the Miwok Tribe who lived on and tended the land designated to become a National Park. Most settlers, including John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, were against the idea of Indigenous communities remaining in Yosemite, as it ruined the perception of an unspoiled landscape. Thus, over the course of decades, settlers attempted to remove Miwok from the region through massacres, forced migrations, arson, and arrests, a campaign underdiscussed to this day. Adams contributed to this effort by deliberately keeping nearby Indigenous peoples and structures out of his photos to support the idea of the pristine Yosemite wilderness, and in doing so, enabled the public to ignore the fact that people were being forcibly removed from Yosemite to present it as pure. The majesty of the untouched Nature in Adams’s photos upheld the myth that the American frontier was free for settling or setting aside. The harm facilitated by these photos is a living legacy in the conservationist movement today, a testament to the danger of failing to preserve truth in Art.

Environmental myths upheld by art remain highly influential. Perhaps the most common image of climate change is a sad polar bear, emaciated and stuck on a melting iceberg. The idea first spread following the release of a paper in 2004 which concluded that “it would be ‘unlikely’ polar bears could survive if the sea ice disappeared completely.” Senator John McCain visited the Arctic and returned talking about the risk of polar bear extinction. Vice President Al Gore used an animation of a polar bear trying to find shelter on a breaking iceberg as a focal point of his documentary An Inconvenient Truth. Soon, polar bears became the face of climate change. However, over time, major issues arose – because the polar bear was so divorced from our everyday reality, an exotic animal in an unfamiliar region, it became easy to dissociate climate change from everyday existence. People treated climate change as a threat to the Arctic, not to the rest of the world or even humans, leading to reduced urgency in addressing threats. Moreover, people began associating polar bears so closely with climate change that even when specific bears suffered from non-climate threats or even did not suffer at all, they were used to advance climate narratives, leading to misinformation, tensions, and retractions. Today, there is an ongoing effort to step away from the reliance on polar bears, and to turn, instead, towards humans.

The usage of Art without Science leads to harm, even if done in the name of Nature. JSO’s action showcases another way of disconnecting Art and Science, this time placing them in opposition, and in doing so, they inspired massive backlash and distorted messaging. Through this, it’s clear that both Art and Science must be valued for equitable and effective change.

Science Relies on Art

For when Art and Science are used intentionally and honestly, social progress can be achieved. Often, that means that scientists must become artists, as exemplified by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring. Today, Silent Spring is recognized as one of the rare books to have tangibly altered society. The public attention the book garnered was so widespread that its publication is often considered the advent of the modern environmental movement. As a direct result of the increased public awareness of the dangers of insecticides, the government was convinced to act, creating the Environmental Protection Agency, passing the Endangered Species Act, and banning many carcinogens, including DDT. The publication of Silent Spring was truly a historical moment.

Carson was perfectly equipped for that moment. As a woman without a PhD, institutional affiliation, or respected field of study, she defied many scientific stereotypes, and instead, had a history writing books, articles, and even radio scripts. She used her appreciation of the literary arts throughout Silent Spring. The book opens, not with a traditional scientific abstract, but with “A Fable for Tomorrow,” an abstract story about a “strange blight” creeping over a “town in the heart of America” inducing unforeseen but avoidable tragedy. Carson equally utilizes storytelling and statistics, understanding the power stemming from the combination of these tools. She even titled the book after a John Keats poem. Through her utilization of both Art and Science in the quest to protect Nature, she synthesized knowledge “into a single image that everyone, scientists and the general public alike, could easily understand.” In doing so, she spawned a movement that survives to this day.

Several other works have combined Science and Art to contribute to a movement, from Dr. Robert Bullard defining the American environmental justice movement with his 1990 book Dumping in Dixie to the marine mammal rights fervor sparked by the 2013 documentary Blackfish. Such works are indicative of an increasing trend in how scientists and environmentalists have taken the lead on using Art to communicate Science. The importance of public engagement in driving change is evident, and thus, initiatives focused on connecting scientists with non-traditional audiences have flourished.

Sometimes, simple visualizations of data have been most effective. The most ubiquitous example are the warming stripes created by Ed Hawkins, showcasing the increase of annual mean global temperature since 1850. By simplifying the data into colors, viewers can intuitively understand the underlying trend. The warming stripes have become iconic, being used knitting patterns, street artworks, logos (see the United States House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis), book covers (see Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book), and more. The beautiful simplicity of the stripes has turned them into a symbol.

Other initiatives are more complex. Xavier Cortada has helmed a “participatory art” campaign known as The Underwater, in which Floridians are encouraged to create public art installations that signify a location’s elevation above sea-level. The project includes paintings, free yard signs, and permanent installations across Miami-Dade County’s public parks and link to resources about the increasing threat of sea level rise in the region.

Meanwhile, underwater statue museums, including statues built of materials that help reestablish populations of corals, fish, and invertebrates have opened off the coasts of Australia and Florida. The projects are unique examples of art directly addressing an environmental threat, as the artificial reefs created by the installations help bolster habitats facing increasing threats of warming, acidification, and bleaching.

Effective environmental communication through art doesn’t have to come from scientists. It doesn’t even have to come from artists – messages can be delivered through our interaction with art, as in the case of JSO. It simply requires a commitment to balancing and preserving both Science and Art and understanding that both are necessary tools for protecting Nature because both pieces are inherent to Nature.

Gratitude for Life

With the context of how Art and Science optimally intersect through Nature, we can finally return to JSO’s action, and the question of why society is willing to protect art but not the environment itself. One can imagine that if the public were more cognizant of humanity and Art’s shared reliance on Nature, more people would be receptive to JSO’s claim that we cannot sit silently as Earth’s natural beauty disappears. Some would still be angry that JSO used the art as a prop, framed their protest antagonistically, and feigned destruction, but such critiques would not be as universal.

Ironically, another piece forgotten in the soup-throwing incident is the painting’s actual meaning. While the financial, societal, and historical importance of the painting was commonly cited by critics, rarely did anyone reflect on the painting’s own message. To Vincent van Gogh, sunflowers represented gratitude. He described his paintings as “almost a cry of anguish while symbolizing gratitude in the rustic sunflower.” Determining what he was grateful for is tougher – perhaps for his friendship with Paul Gaugin, whose room he decorated with sunflower paintings. More likely, though, the sunflowers represented gratitude for life. The sunflowers across van Gogh’s series are depicted at multiple life stages, from bud to blossom to decay, reflecting how there is beauty worth admiring and preserving inherent to all life in the natural world, no matter its condition. Such a theme was likely personal to van Gogh, who painted much of his Sunflower series throughout difficult times in his life. To him, perhaps the “rustic” nature of the sunflower, viewable from any field or window, represented the simplicity and accessibility of beauty in even the most ordinary aspects of our world.

Van Gogh saw the sunflower as a reminder that nature is a healing force, that life can be worth living, that beauty is alive. He held onto the radiant presence of the sunflower throughout the darkest moments of his life, and he left behind their visages as a reminder of the world’s natural beauty and of the individual connection one can make with the subtle resplendency of Earth. Because he understood this, I think that he would have empathized with a generation who can see the Earth’s beauty irrevocably slipping away. I think that he would have respected those that wouldn’t accept that an oil-based facsimile of Nature was being deified, while Nature herself was being sacrificed for oil.

Success and Failure

Judging JSO’s action on whether it was able to establish a strong connection between Art and the environment, this action is largely a failure. Most discussion around the protest was argumentative, and members of both the public and the artistic community were seemingly turned off JSO, resulting in little opportunity to coalesce around a shared love of Nature. But it’s generous to assert that such a response was JSO’s primary goal, at least this time. Weeks before, JSO had protested more along this messaging, covering John Constable’s “The Hay Wain” with a climate disaster-themed parody, but that action got comparatively little press. The choice to pivot towards a more inflammatory tactic implies JSO intended this protest to play on the radical flank effect, in which an action that everyone talks about pushes sympathetic people towards moderate or institutional action, even if they don’t support the radical action. Under this plan, all the negative attention and the lack of artistic and environmental unity would be irrelevant – actually, it would be intended.

In fact, JSO seems to believe that this action has done all it needed to – members of the group tout it as a success, noting that it spurred more press mentions of the word “climate” than the devastating floods that covered 1/3rd of Pakistan in 2022, cementing the idea that the intention was to gain attention. And notably, thanks to promises by recently-elected Prime Minister Kier Starmer in July, JSO’s original goal of getting the UK to end new fossil fuel leases has been met. While it is difficult to draw causality between this action and Starmer’s decision, it can certainly be interpreted as having ignited the movement’s momentum. Meanwhile, JSO has recently chosen to focus on actions more traditionally connected to climate change such as paint-bombing private jets, blocking traffic, and disrupting airports, in an apparent shift towards actions more easily connected to carbon emissions.

Still, it hurts to see the underlying idea behind the painting protests abandoned, if only because the principle JSO ostensibly advocated for was important. All art is ecological, van Gogh’s Sunflowers especially, and the hypocrisy in treating it as something we cannot afford to let even be perceived as damaged, all while children see their futures burn is asinine.

With other goals successfully met, what is left is to reform the broken relationships between us and Nature, and this must be done by connecting Art and Science. Scientists must engage with Art to better communicate the existential harm of climate change. Artists must reconnect their work with Science and Nature to understand that protecting art, achievement, and humanity requires urgent action. And we all must recognize that both Science and Art are tools to inspire environmental understanding and action, and each must play a role in ensuring there is an equitable future on Earth in which we can enjoy both disciplines and thrive.

Such a future requires change, both in how we think about ourselves, Nature, and Art, and in how our society values a picture frame above children’s lives. Structural and societal reformation is radical, so maybe it deserves an action like JSO’s. For of course, radical actions, even non-violent ones like damaging a priceless painting, are never initially accepted – that’s what makes them disruptive (see Rian Johnson’s Glass Onion). The capitalistic status quo is exactly what has produced conditions in which Nature can no longer support humans, and so, the status quo cannot continue.

Because, in reality, our fossil fuel use is not sacrificing the Earth. Even if the climate warms 10 degrees and oceans rise by 100 feet, the Earth will survive. We are sacrificing our ability to enjoy the Earth, to remain part of Nature, and to honor its beauty through art.

A mentor once told me “we contain multitudes both within art and within science" – in other words, we are full of Art and Life. But unless we act now, we will soon lose access to both.

Isaac Olson is a graduate student studying science communication and oceanography at the University of Washington.